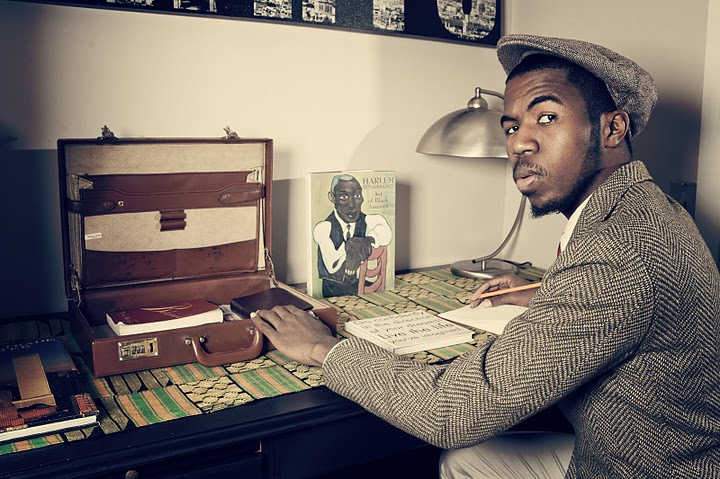

Poet to Watch: Joshua Bennett

Joshua Bennett hails from Yonkers, NY. He is a doctoral candidate in the English Department at Princeton University, and has received fellowships from the Ford Foundation, the Center for the Study of Social Difference at Columbia University, the Bread Loaf Environmental Writers Conference, and the Callaloo Creative Writing Workshop. Winner of the 2014 Lucille Clifton Poetry Prize, his work has been published or is forthcoming in Anti-, Blackbird, Callaloo, Drunken Boat, Obsidian and elsewhere. Joshua is also the founding editor of Kinfolks: a journal of black expression.

Glappitova: Joshua, it’s a pleasure having you here to interview. You’ve accomplished so much in your tenure on this planet and are not even in your 30s! Let’s start from the very beginning: Why poetry? Why words?

Joshua: Trust, it’s a pleasure just to be in the space. If my mother is to be believed—and she is, given all the empirical evidence I have to work with—I have been writing poetry in some form since I was about five years old. Now, as then, I think of wordcraft not only as a means through which i might render on the page the world I have inside of my head, but also that I might have a beautiful object to share with friends and strangers alike. I come from a family of charismatic, performative folk. We sing and yell at each other and gossip and pray with a certain kind of fire. In my most recent work, I find myself trying to make sense of that particular set of relations, that is, the home that made whatever I am now.

G: So, in some ways poetry is a reflection of what home means to you and a way for you to share “home” as a concept, a belief system, with other people. Dopeness. How do you get from that space of writing poetry down to the space of oral poetics? You mentioned prayer and gossip above, so naturally communication is always first and foremost an oral art form. But poetry is so private, no? When did you find yourself on the stage and what did that first feel like?

J: Well, as a bit of historical context, I want to mention that I first found myself on the stage as an actor in a starring role in a church play. All I remember really are the blue pajamas, which I loved. I also sang in the choir, and would sometimes recite scriptures from memory in Sunday school, which wasn’t necessarily a stage, but it was school, which has always also been a stage for me. That all being said, my first time performing poetry on stage was right after I had finished doing some homework in a public library in Yonkers.. My mom was there too. The library was hosting a poetry slam downstairs, and she encouraged me to sign up. I recited the only poem I had committed to memory at that time (no lie, it was called “Hope and Love” or something to that effect) and won second place. The person that won the whole thing was a dude named Marcus. I enjoyed his work very much.

From there, it would be about three years before I would memorize and perform a poem in the style for which most people that have encountered my writing know me now. It was a Sunday, I think, and I had just attended a Hurricane Katrina Relief Benefit at Sarah Lawrence College the day before. There, I watched a two-hour performance from spoken word poets from across New York City, many from an organization by the name of Urban Word NYC. I was so utterly enthralled by this performance (and I mean like, this was a low-key transcendental experience) I purchased an Urban Word NYC t-shirt and CD and wrote a three-minute performance piece the next day. From there, I started entering poetry slams in Manhattan, made the 2006 Urban Word NYC youth slam team, and my entire life changed.

Oh, and to answer the second part of your question, those first performances felt like having a conversation with a 30 or 40 or 1000 people at once. Even if they didn’t speak back, you could hear their laughs or snaps or watch their expressions change. It felt like I was part of this boundless ecosystem, and though I was at the front, I wasn’t necessarily the center. But I was still glowing, you know? I still felt a certain electricity in those spaces that evades language.

G: So we fast forward and you’re talking to your manager. I think we need to briefly go over how you as a poet even got a manager (haha) and then, too, what you talked to her about? You had a project in mind that turned into another family.

J: Sure! So I ended up working with my manager, Latoya Bennett-Johnson, after my performance at The White House in 2009. I decided around that point that I should start thinking differently about the work, and make a concerted effort to try to turn my love for performance into something resembling a career. So I reached out to her, knowing that she already had all sorts of experience managing artists as an events director at the corporate level, and it turned out to be one of the best decisions I have ever made. Latoya has always gone to bat for me, since day one. She’s not afraid to fail. She listens. Knowing this about her, I gave her a call in September of 2010 to pitch the idea of starting a poetry collective. That idea would eventually turn into The Strivers Row, LLC an artist management company and booking agency based out of New York City. We just recently signed a new wave of clients, and have some great events lined up for the near future. I’m fairly active on the business end nowadays, and I appreciate, more than anything, the patience that Latoya and Marcus (who is the creative director over at TSR) have with me. I’m a lot to deal with sometimes. Most of the time. Pretty much all the time really.

G: How do you go about finding artists for Strivers Row? When I discovered you guys fairly recently it seemed as though you were more a poetry group, a collective so to speak, than individual artists coming together to work collaboratively. I even did a Poet to Watch of Alysia Harris, who is a part of The Strivers Row. How did you find the first poets and how did you go about finding this new wave of clients? What do you look for?

J: Most of our approach to building the company at the level of clientele is the product of open conversation. During the first wave of TSR poets, pretty much every single one of those folks were people I knew and had worked with before. Much of what we’re thinking about now is how to expand the roster to a larger size while maintaining a certain kind of collegiality and collaborative spirit that has always been the goal. As far as a vetting process, we do our best to keep our ear to the ground to see who’s doing interesting work in the field. More than anything, we’re looking for imagination, daring, and versatility in the artists that we work with. I think you’ll dig a lot of those folks that will be coming aboard. They are some of my favorite writers in the world.

G: Is this an international effort? Are you reaching across the globe to find talent?

J: I can’t speak on that at present though it’s a really good question and I love you. Put differently, we’re always on the lookout for folks doing interesting work, no matter where in the world they might be.

G: What have you learned about the business world as it relates to keeping your craft intact? Have you ever had to sacrifice the entrepreneurial spirit in order to maintain your artistry or vice-versa? Do you even consider yourself an entrepreneur?

J: I suppose I’ve learned to take myself seriously, and place a certain value on my labor. Though I certainly write for the love of craft, and because it brings me great joy, writing and performing professionally—which is also to say, using poems to pay rent and work toward the slow disintegration of this student loan debt (amen)—has taught me that I have to be willing to make an argument for the place of my work, and the work of folks in my tradition, to contend with those that don’t think it’s valuable at all. I don’t think of myself as an entrepreneur, really. I just like to dream things up and see if folks are interested in building things with me. I’m true to my childhood self in that way. Strivers, as well as a project like Kinfolks Quarterly—the literary journal I started with my partner, eve ewing, and a group of our friends—are in part the result of my ongoing commitment to creating spaces for the kind of work I love and want to see more of in the world. Some might call that entrepreneurial. I just think of it as a practice of living.

G: Tell us more about Kinfolks. How long has it been around and what types of work do you look for? I imagine it’s difficult to run an online journal but you do have quite a few people working with you and eve.

J: Kinfolks started as an idea I shared with an old friend from college. After a few months of conversation, it became clear that we had divergent ideas regarding the best way to give life to the largely inchoate formulation we’d thought through together so we parted ways. Eventually, I sat down with eve to talk about the vision for the journal and her singular brilliance helped give it a certain kind of coherence. I then reached out to what now constitutes our editorial board, all of whom are writers and thinkers I admire greatly. These folks are doing destabilizing, necessary work in the field of American letters, and have all expressed, time and time again, their commitment to seeing that field flourish, and to giving proper attention to historically excluded voices.

G: Let’s talk about your own work. What have you been working on as a poet? What is the latest written project that you are working on? How do you juggle the written with the spoken?

J: More recently, I’ve been working on a larger manuscript, tentatively titled The Sobbing School. In the book, I’m primarily interested in thinking about & through despair, or more precisely blueness, as an organizing principle of both my social and interior life. The book is also about my relationship to school as a social institution; how I think of myself as being both marked and marred by my experiences with formal education, though school has always also been a site of kinship and self-exploration. I do my best to juggle the written with the spoken by reading as much from the manuscript at performances as I can, and also by putting work on the page that has the same sort of playfulness and musicality as my poems written specifically for the stage.

G: And as far as community building, how are you using your scholarship and poetic interest to get people together?

J: I don’t as often as I would like to. Which is part of why it always brings me such great to joy to curate a Kinfolks reading or participate in Strivers Row showcases. Both are events that center the arts, but what’s more they produce these moments where folks can just be together and drink delicious beverages and listen to poems. I want to continue to create spaces like that for as long as I live.

Outside of gathering in a physical sense, I’m also currently working on an anthology project which centers around the way black poets have historically written about their relationship to death. As we see over and over in our present moment, black death is normative. It’s not aberrational. Given the information we have about the kinds of unrelenting violence that black folks in the U.S. context have faced since their arrival on this continent, how can we think critically about the ways they have written about and against such violence? How have they written in offense of the death that encroaches on all sides? To riff on my friend and colleague, Ashon Crawley, how have they lived and dreamed otherwise?

G: Thank you so much for taking the time out to do this. If people want to learn more about what you do as a poet and leader in this poetry world, where can they reach you?

J: Well first, I just want to thank you, Phillip, for your generosity and imagination. It’s an honor just to be in conversation. I think aloud most frequently on Twitter at @sirjoshbennett so folks can reach me there if they feel so led.

Glappitnova unites influencers and talent from different industries through storytelling, performances, classes, and events for one crazy 8 day experience in Chicago.The opinions expressed here by Glappitnova.com contributors are their own, not those of Glappitnova.com.

comments

AI Will Impact 400 Million Jobs by 2030 So Let’s Prepare

AI Will Impact 400 Million Jobs by 2030 So Let’s Prepare

From Redmoon to Newmoon Theater Announcing Alex Balestrieri on The Global Committee

From Redmoon to Newmoon Theater Announcing Alex Balestrieri on The Global Committee

Announcing Wingsuiter and Curator Kody Madro on The Global Committee

Announcing Wingsuiter and Curator Kody Madro on The Global Committee

Glappitnova 2.0

Glappitnova 2.0

Announcing Creative and Engineer Josh Onwordi On The Global Committee

Announcing Creative and Engineer Josh Onwordi On The Global Committee

Announcing Global Healthcare Executive Samantha Thaver on the Glappitnova Global Committee

Announcing Global Healthcare Executive Samantha Thaver on the Glappitnova Global Committee

Announcing Illini Track Star Turned Entrepreneur Jonathan Wells On The Global Committee

Announcing Illini Track Star Turned Entrepreneur Jonathan Wells On The Global Committee

Announcing Ella McCann On The Glappitnova Global Committee

Announcing Ella McCann On The Glappitnova Global Committee

Announcing Cultural Executive Andrew Harris On The Global Committee

Announcing Cultural Executive Andrew Harris On The Global Committee

Announcing Matt Carney Of Root Tulsa On The Glappitnova Committee

Announcing Matt Carney Of Root Tulsa On The Glappitnova Committee

Announcing Jerica D. Wortham Tulsa On The Global Committee

Announcing Jerica D. Wortham Tulsa On The Global Committee

Announcing Michael Grogan Tulsa On The Glappitnova Global Committee

Announcing Michael Grogan Tulsa On The Glappitnova Global Committee

Community Development Tips For Millennial Audiences, Wanna Come?

Community Development Tips For Millennial Audiences, Wanna Come?

The Advertising Industry Is Working Scared

The Advertising Industry Is Working Scared

Announcing Our New Platform, Foonova

Announcing Our New Platform, Foonova

1 Comment

Poet to Watch: Joshua Bennett - All Industries ...

–[…] Joshua Bennett hails from Yonkers, NY. He is a doctoral candidate in the English Department at Princeton University, and has received fellowships from the Ford Foundation, the Center… […]